Civil Rights icon Amelia Boynton Robinson dies at 104

Published 11:30 am Wednesday, August 26, 2015

Amelia Boynton Robinson is shown on the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday with President Barack Obama and U.S. Rep. John Lewis.

By JUSTIN AVERETTE and BLAKE DESHAZO | Staff Writers

Civil rights icon Amelia Boynton Robinson has died. She was 104.

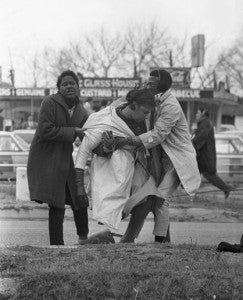

The country woke up the morning of March 8, 1965, with a photo of Boynton Robinson across the front pages of newspapers from coast to coast. The 53-year-old mother had been beaten unconscious during what is now known as Bloody Sunday.

That image and others of peaceful protestors being attacked by Alabama State Troopers and Sheriff Jim Clark’s deputies showed the world how serious the fight for voting rights had become and resulted in a groundswell of support for the Selma to Montgomery march and, eventually, the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

While Boynton Robinson moved from Selma decades ago, there will always be a place for the matriarch of the Voting Rights Movement in the Queen City. Several years ago, the city of Selma has named a street in honor of her and her late husband, Sam Boynton.

Selma City Councilwoman Bennie Ruth Crenshaw called her a mentor and inspiration.

“What I will remember most about Mrs. Boynton is her humble spirit, her love for mankind and the many sacrifices she and her husband made for freedom, the right to vote and justice for all,” Crenshaw said.

Boynton Robinson was born Aug. 18, 1911, in Savannah, Ga. to George and Anna Platts. She was one of 10 children and started campaigning for women’s suffrage at an early age, working with her mother to hand out voting information to women from their horse and buggy in 1920.

After graduating from Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), she moved to Selma with Sam, settling in a home on Lapsley Street. A registered voter since 1932, she fought to make sure everyone had the same right to participate in the political process.

“She was one of the few people who came to Selma in the thirties and continued in the movement until the day she died. Every time there was a breath of life and energy in her body, she was just extremely concerned for young people,” said lawyer and activist Rose Sanders. “No one person in Selma contributed more to civil rights and human rights than the Boynton family, not just Mrs. Boynton but her husband.”

Frederick D. Reese, now the sole surviving member of the Courageous Eight, knew Boynton Robinson well.

“She was a very delightful person to be around, and certainly she had many great things that she has done,” Reese said. “And of course, she was always a great person to be around, looking to the future and making things better for our community and for all people in general.”

Above any single memory of Boynton Robinson, Reese said he would remember her determination to stand by what she believed was right.

“My fondest memory of her would be her determination to stand by her convictions, that whatever she felt was right not only for herself but for the people around her,” Reese said. “She took a stand, and she did not back down from what she felt was right and good for all of the people.”

In 1964, Boynton Robinson became the first black woman to run for Congress in Alabama. She garnered 10 percent of the votes at a time when only 1 percent of the voting population was made up of African Americans.

Almost five months to the day after being beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Boynton Robinson was invited to Washington, D.C. to see President Lyndon B. Johnson sign the Voting Rights Act on Aug. 6, 1965, giving everyone, regardless of their skin color, the right to vote.

“Amelia Boynton challenged an unfair and unjust system that kept African-Americans from exercising their constitutionally protected right to vote,” said U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell earlier this year. Sewell is a Selma native and represents Alabama’s 7th Congressional District as the state’s first black Congresswoman. “She paved the way for me to accomplish all that I have today, and her legacy should inspire us not to take any of our rights for granted.”

Boynton Robinson attended President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address in January as Sewell’s guest of honor.

Sewell tells a story of Boynton Robinson being told repeatedly by a group of young people, “We stand on your shoulders.” The civil rights icon implored them to, “Get off my shoulders — there’s plenty of work to do.”

A few weeks later, Boynton Robinson crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge with Obama and U.S. Congressman John Lewis for the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

“This nation has lost a crusader, a warrior and a fighter for justice … Mrs. Boynton was involved in the struggle for voting rights long before I was even born,” said Lewis, who led the Bloody Sunday march with the late Rev. Hosea Williams. “She was a co-founder of the Dallas County Voters League in 1933 and held voter registration drives throughout the darkest, most dangerous decades of segregation in Alabama.”

Through even the most difficult times, Lewis said Boynton Robinson always kept the faith.

“It was a great pleasure to get to know her and to work with her in our grassroots effort to transform America. Amelia Boynton never got weary. She never gave up. She never gave in,” Lewis said. “At over 104 years old, Mrs. Amelia Boynton lived a well spent life helping to make Alabama and our nation a better place. … She will be deeply missed, but her legacy and her contribution will be remembered always.”

President Obama released a statement through The White House talking about marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge with Boynton Robinson: “Earlier this year, in Selma, Michelle and I had the honor to walk with Amelia and other foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. She was a strong, as hopeful, and as indomitable of spirit — as quintessentially American — as I’m sure she was that day 50 years ago.”

The President added that the best way to honor her legacy would be to continue the work she believed in so strongly.

“To honor the legacy of an American hero like Amelia Boynton requires only that we follow her example — that all of us fight to protect everyone’s right to vote,” Obama’s statement read.

Crenshaw said another way to honor the Boyntons would be to restore their home and turn it into a museum. The residence, now in deplorable condition, housed many who helped with the voting rights movement and was also where the letter inviting King to Selma was written in late December of 1964.

“I loved her, and she often told me I made her proud. I have done many events to honor Sam and Amelia Boynton, but the most gratifying of all would be to see the renovation of her home come to fruition,” Crenshaw said.