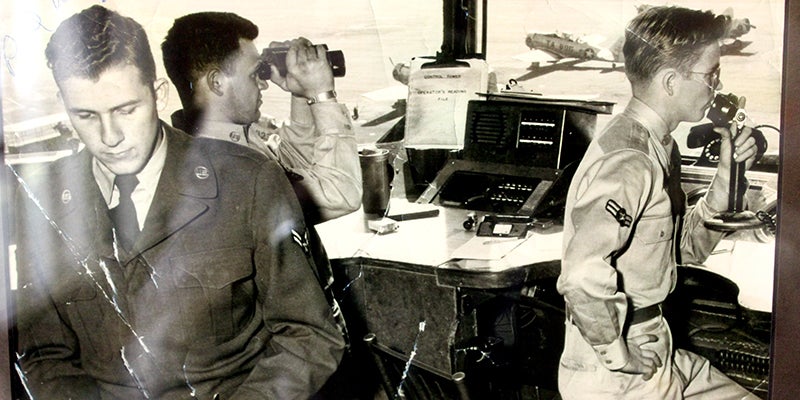

Corrigan reflects as student at Craig Air Force Base

Published 11:44 pm Friday, September 27, 2019

Editor’s note: This is the second of a three-part series on Craig Field and its past role and future prospects as an economic development engine for Selma and Dallas County. In the final installment, we take a look at Craig’s future and the efforts being made to market it regionally and nationally.

As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, and the war in Korea throttled down just as the fighting in Vietnam ramped up, Craig Air Force Base steadily saw its role as a provider of capable pilots increase as the demand for jet and bomber pilots steadily increased.

According to Craig Field Airport and Industrial Authority (CFAIA) Executive Director Jim Corrigan, many of the men who trained in Selma were tossed directly into combat, though a lot still had to be worked out with the military’s new jet wings.

According to Corrigan, the original jets weren’t outfitted with guns, an issue that had to be remedied before the aircrafts could be used in combat.

But the Craig-trained pilots who flew in Vietnam brought more to the table than knowledge and ability. Once the war in Vietnam began coming to a close, many of those fighters were called home and placed in non-flight jobs, some as instructors for the next generation of Craig pilots.

“They had plenty of war stories and plenty of experience,” Corrigan said of the pilots-turned-instructors. “When the instructors talked, you listened. There was so much to learn from those guys.”

Corrigan, who would become a student at Craig shortly before its closing, remembered that those instructors brought with them a wealth of practical experience from the field, which was invaluable to the new recruits.

“I got to learn a bunch from those guys that went to Vietnam,” Corrigan said.

But the draw down left some feeling as if their wings had been clipped and, after a short stint as an instructor, they departed for commercial airlines.

While the Vietnam War saw a boom of activity at Craig, Corrigan noted that when he arrived at the base in 1975 it was moving at “full steam.”

At that time, Corrigan remembers there being eight classes of 25 students cycling through the base at a time, clocking experience with T-37s and T-38s, and seeing a dozen aircrafts flying overhead at a time.

“It was a busy place in those days,” Corrigan said.

Beyond the flurry of activity, however, Corrigan asserts that the pilots who trained at Craig were the reason that the U.S. Air Force became such a powerful branch of the military.

“The reason the Air Force has been so lethal over the years is because of training,” Corrigan said. “We had the best training in the world. For a lot of people, it started right here at Craig.”

At one point during the mid-1970s, Craig was among the busiest airports in the world, with more than 93,000 flight hours and 455,000 aircraft movements, but the boom of the Vietnam years slowly gave way to the bust of the post-war era, when the need for pilots and fighters was greatly diminished.

Around 1976, as the administration of U.S. President Jimmy Carter began looking at closing bases, the people of Selma launched an effort to save the base, which had become so important to the city’s life and livelihood.

“I think they made a good effort,” Corrigan said. “They knew the implications of closing this base.”

That knowledge can be clearly seen in the archives stowed away in Craig’s museum. An oversized binder holds letters from local leaders and residents pleading with the federal government to keep the base open. In an effort to sway federal decision there was also research conducted to show the economic impact the base had on the area, as well as the impact that its closing might have.

According to data collected at the time, Craig Air Force Base had an annual military and civilian payroll of more than $32 million, over $4 million more than the county’s payroll at the time.

Additionally, in 1975, the base produced about $9.2 million in contract services and materials, roughly 40 percent of which was furnished by suppliers and contractors in Dallas County. If the base were closed, the report stated, the county would lose about $3.3 million in federal dollars and nearly half of those employed by the base would enter the pool of unemployed.

The study also projected that nearly 30 percent of Dallas County’s population at the time would leave the county as a result of the base’s closure, resulting in the unemployment rate soaring to nearly 22 percent.

In its efforts to save the base, local government leaders filed a lawsuit against the federal government to take back ownership of the land the base sat on, but it was all to no avail. Despite having been previously converted into a state-of-the-art aircraft maintenance depot, the base was closed in 1977.

Along with Craig, operations were shuddered Moody Air Force Base in Georgia and Webb Air Force Base in Texas, which combined had the capability of churning out more than 3,000 pilots every year.

Corrigan remembers those final days.

“It was really a sad time,” Corrigan said. “Everybody liked Craig. Everybody liked Selma and the Alabama River and all the local hangouts.”

Corrigan recalled how the pilots had to fly the aircrafts stationed at Craig to other bases, then fly back commercially and repeat the process until all of the planes and jets had been shipped off to other bases.

During the years following Craig’s closure, Corrigan continued flying. He flew T-38s as an instructor in Texas, flew F-16s in Europe and Korea and eventually found himself at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery.

Travelling to Maxwell, Corrigan passed through Selma and said it was obvious how devastating Craig’s closure had been to the city and county.

“You could just see the impact that closing Craig had on this economy,” Corrigan said. “Selma opened its arms to Craig – to see it lose Craig, and see the results nine years later, depressed me. This city didn’t deserve that.”

There was no shortage of explanations as to why the base was closing. Selma’s mayor at the time, Joseph Smitherman, stated that the closure was due to the fact that Craig didn’t have a third runway; Corrigan believes it was largely due to President Carter’s desire to reduce defense spending in the face of what was considered a decreased need for pilots.

In an article in the Los Angeles Times, which detailed the closure and the city’s fight to keep the base, a local resident was quoted as saying that the closure of Selma’s base felt like “having your heart ripped out.”

Upon closure, the site was sold to the CFAIA, which continues to operate it today, but it would be years before activity returned to the site and even more before Corrigan returned to oversee its resurrection.