EPC report: Black Belt lacks access to healthcare

Published 8:00 am Tuesday, October 13, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On Monday, the University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center (EPC) released the next chapter in its series on the Black Belt, entitled “Healthcare: A Key Challenge in Alabama’s Black Belt,” which explored healthcare access in the region.

The study looked at a number of health care-related issues in the region and across the state, including the number of hospital beds per 1,000 residents, the rate of change in premature deaths, the rate of preventable hospital admissions and more, and found that, while the Black Belt lags in some areas, the entire state is suffering.

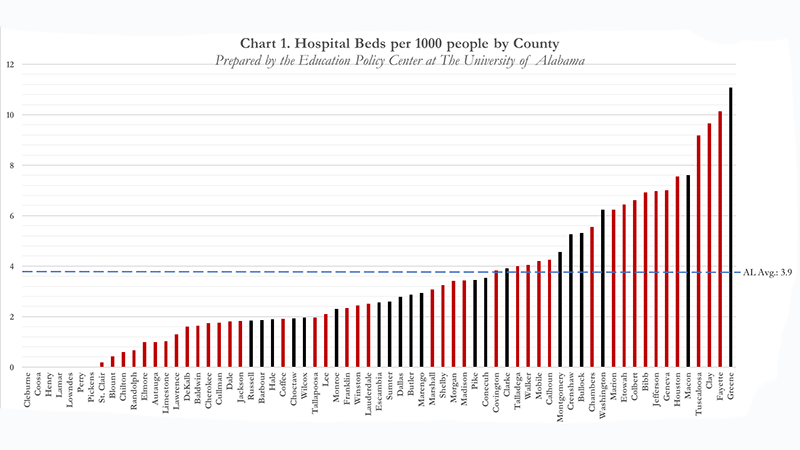

As far as hospital beds are concerned, the EPC’s research found that 17 of the counties listed as part of Alabama’s Black Belt were lagging the state average of 3.9 beds per 1,000 residents, with four counties – Lamar, Lowndes, Perry and Pickens county – showing no available beds due to the lack of a local hospital.

Nationwide, Alabama ranks 13th for the number of hospital beds per 1,000 residents.

While the EPC’s study found that the number of hospital beds in the Black Belt is proportional to its total population – the Black Belt makes up 14 percent of the state’s population and has 13 percent of its hospital beds – it noted that most of those counties are underserved.

The report states that the data indicates that “Black Belt residents lack physical access to healthcare.”

On top of the fact that rural hospitals continue to close – as of February, the state has lost seven – and the state continues to refuse to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), researchers noted that healthcare in the Black Belt is

under more strain now than ever.”

For EPC Director Stephen Katsinas, the lack of access to healthcare in the Black Belt and across the state can largely be placed at the feet of former Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley, who refused to expand Medicaid, which researchers said has cost the state billions in federal funding and economic activity.

“Robert Bentley’s choice not to take the ACA funding in 2014 when the federal government was offering such generous matching inducements is easily the single worst decision made by an Alabama Governor since George Wallace’s infamous ‘stand in the in the schoolhouse door’ to bar African Americans from enrolling at The University of Alabama in 1963,” Katsinas said. “The $3.3 billion in missing funds would have simultaneously stabilized Alabama’s volatile General Revenue Fund and thus protect education funding, while resulting in better health care outcomes statewide, for rural residents generally, and rural Black Belt residents specifically.”

Joining Katsinas and the EPC researchers for Monday’s press conference were U.S. Sen. Doug Jones, D-AL, and Alabama Rep. Kyle South, R-Fayette, who had differing opinions on how the state should address healthcare inequities in the Black Belt.

For his part, Jones chided the fact that there has been “a lack of resources and attention” paid to the Black Belt and agreed with Katsinas that the state’s refusal to expand Medicaid has done immense damage to low-income Alabamians.

“And it was all for purely political reasons,” Jones said of Bentley’s decision not to expand Medicaid, a program that right now roughly 1.2 million Alabamians qualify for despite the state’s restrictive guidelines.

Jones also worried about U.S. President Donald Trump’s attempts to eliminate the landmark healthcare bill, which would impact nearly 1 million Alabamians with pre-existing conditions and worsen already bad health outcomes for the most vulnerable populations.

South, however, noted moves that the state has already made to increase access in rural areas, including expanding the scope of practice of nurse practitioners and expanding partnerships with the University of Alabama-Birmingham (UAB), but would not endorse a call for the state to expand Medicaid.

“I’m not going to argue the other side of Medicaid expansion,” South said. “I think a lot of it is dependent on whether the federal government makes some moves and returns those generous matches.”

Jones currently has a bill in the Senate that would extend the original three-year, 100 percent federal funding match to the 13 Medicaid holdout states.